Cura is one of the most common slicers for a good reason. For this article, I am working with the 2.6 beta. The goal is to provide a simple, approachable interface to start with. It contains simple quick print settings for novices, then allows you to switch to expert mode and dig in. The default exposed options are good for switching to more advanced materials, but the magic comes in with the hundreds of options available behind the default interface.

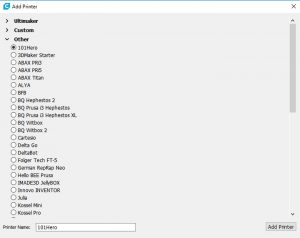

When you launch Cura for the first time, you will be prompted to define your printer profile. They have a good number of pre-determined printer profiles set for you, so if you have one of the more common pieces of hardware, you’ll be set quick. A notable exemption is the Aleph Objects Taz series. This is likely due to the modified version of Cura that Aleph Objects distributes, with utilities for firmware modification to their printers along with material profiles tested for their machines.

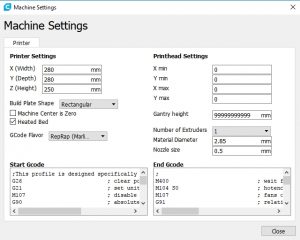

If you need a custom profile, they have all the normal options. Bed shape and size, maximum height, heated bed, number of extruders, and offset parameters for multiple extruders. You can configure starting and ending g-code as well as flavor of g-code to be generated. Nozzle size and default filament diameter can also be configured.

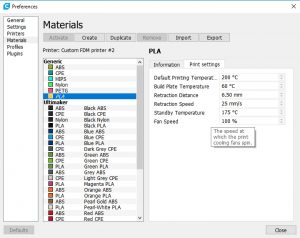

Next you move on to materials. They have a number of defaults set for the Ultimaker brand machines and filaments, since they are the primary developers of the software, however you can easily add your own as well. When you define a new material, you can add information such as brand, density, cost, and other descriptions as well as print settings. The print settings per material here are very limited. You can only set the extruder and bed temperature, retraction speed and distance, standby temperature, and fan speed. Especially when dealing with flexible filaments and exotics, speed configuration is a must.

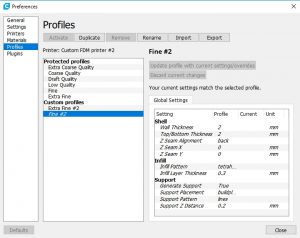

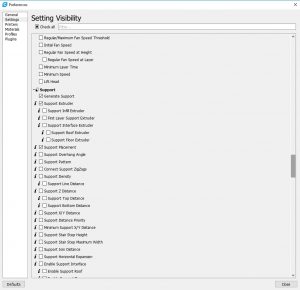

Because of the limitation with direct material settings above, I personally tend to use profiles as a global configuration for materials and quality settings. The profiles segment allows you to store all custom settings in a profile. This can be as simple or complex as you’d like with the ability to store any of the 200+ configuration options available.

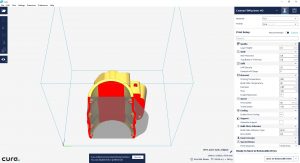

For general usability, several features stand out. The first is part highlighting. When you load a model with steep overhangs, they are highlighted in red. You can easily move and rotate the model using the tools on the left hand side of the screen. Some features I miss from other slicers is the ability to enter manual rotation angles, or to specify a mesh to place on the build plate. In place of those, you can enable snap rotation where it rotates in set increments, and lay flat which will fine tune the current rotation for the best bed contact. I find this to be a bit hit and miss with many of the models I have worked with. You can scale the model precisely, mirror it, and move it around the build plate.

One of the nicer features here is the ability to assign individual properties to each part if you have multiple models loaded. This is something that has been getting developed more recently and has been a huge advantage in multi-part runs in many cases.

The general workflow in normal usage will be to load and place models, then set rotation. From there, select the material for your temperature setup, then your print profile for the in-depth settings. As Cura slices in the background after every change, you can then go immediately to layer view and take a look at the generated supports and bed adhesion options. If you are satisfied with the profile selected, then either print directly from Cura to a supported printer or save the g-code to a file for printing through the SD card or print server such as Repetiere or OctoPi.

Overall Cura is a solid piece of software with a large active community. It is one of the leaders for a reason and continues to pioneer new features at an astounding rate. The basics will get you printing, but the detail is there for most scenarios you could run across.